In New York, a fan buys snacks to eat while watching a Giants game. In rural Vietnam, a mother purchases her daughter’s first deodorant in a local store. Despite being thousands of miles apart, these consumers are experiencing what the marketing community calls the “moment of truth”: the point at which a shopper chooses one brand over another. Across the globe this moment varies, not only depending on product but country.

One shopping trolley doesn’t fit all, but by identifying demands shared by consumers on a global scale marketers and brands can plan for the future. In the modern world, the demand for convenience is the driving force behind consumer behaviour and trends seen across the globe.

Within arm’s reach

Ease of access is vital when it comes to fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) shopping. No one wants to travel a mile out of their way for a pint of milk after work. Rather than condemning themselves to a life of black tea, shoppers seek a store nearby. In China, for example, 79% of shoppers favour a store close to home; the same goes for us Brits, with half the population citing location as the key reason for choosing their supermarket, ahead of price and range.

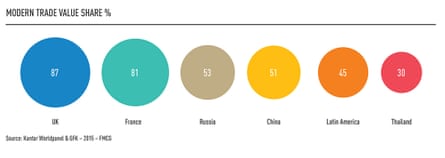

The way we shop varies hugely across the globe. In the Philippines and Thailand modern trade such as supermarkets accounts for only 30% of sales, compared with around 80% in western Europe.

In part, this is because of logistics. For example, the Indonesia archipelago has more than 18,000 islands, creating difficulties for brands in making themselves accessible to shoppers. Yoghurt drink Yakult has solved this problem by making its brand available via more than 5,000 Yakult Ladies, who deliver the products to individuals in their homes. The product is sold in 31 countries around the world, but Yakult Ladies only sell and distribute in Asian countries. The dedicated workforce of mainly women fulfils the dual role of brand ambassador and product deliverer.

The Uberisation of FMCG

In the FMCG market, technology is redefining what it means to “go” shopping. Lines between the physical and digital worlds are blurring. Shoppers are growing accustomed to the benefits of digital in other retail settings and are beginning to expect them in grocery as well. Mobile accessibility is changing how shoppers interact with e-commerce, and using a phone or tablet is becoming the normal way to shop online. By 2018 it is projected that 71% of global internet users will have a smartphone.

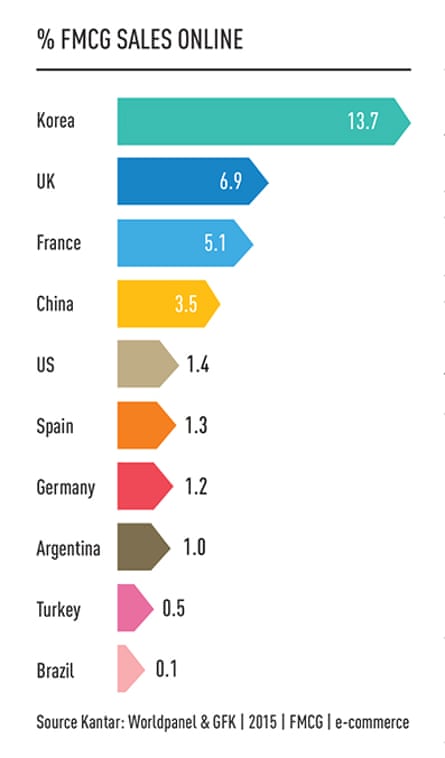

Whether accessed through mobile or more traditional computers, e-commerce FMCG sales continue to grow strongly, up by 15% globally in 2015. South Koreans lead the way, buying 14% of their groceries online. What is perhaps surprising is how the take-up of e-commerce doesn’t necessarily follow the national take-up of technologies such as broadband. While the French and British have embraced online grocery shopping, it has yet to make a serious impact in the US. Latin America and large parts of Asia need to address issues of infrastructure and geography before e-commerce can thrive. Despite these challenges, e-commerce is projected to command a global 9% share of FMCG sales by 2025.

However, the trickiness comes when these virtual transactions become physical objects in the shopper’s hand. The cost of picking, packing and delivery can potentially wipe out any retailer margin. French retailers have had success in easing some of these costs and growing the online channel through the “drive” model, where shoppers come to the store to pick up their pre-ordered baskets.

Amazon clearly sees an opportunity in this market, rolling out same-day delivery options in the UK. While not necessarily cheap, quick delivery brings more shopping experiences, such as “dinner for tonight” into the e-commerce realm. While fast delivery by drone looks some way off, retailers like Amazon are also exploring working in an Uber style with freelance drivers, like Deliveroo and UberEATS are doing for restaurants.

The ‘Lidl’ effect

Thanks to low prices and agile advertising, discount retailers have thrived in Europe in recent years. In opening more stores the retailers have increased their physical availability and convenience.

Some consumers consider the smaller range of products on the shelves in discount retailers to be a good thing. Shoppers, usually overwhelmed by choice, have much simpler decisions to make when faced with only a few varieties of cola or toilet roll. Whether or not the consumer prefers it, having fewer lines on the shelf and in the warehouse definitely makes for a leaner, lower-cost business, ultimately passed on in cheaper prices.

Mainstream retailers have reacted by also streamlining their offerings. For example, last year Tesco removed Carlsberg from shops in a bid to reduce the number of beer brands on its shelves. As the big retailers reduce lines, discounters may well consider introducing more branded and premium own-label items to widen appeal and avoid a growth plateau. In the UK, only 10% of lines in discounters are brands, however in Germany, where discounters possess around a quarter of the market, these stores are around 30% branded.

The ultimate inconvenience for a shopper is when the retailer is closed, a problem that has been solved by one entrepreneur who has opened Sweden’s first unstaffed convenience store. Open 24 hours a day, seven days a week the store has no staff, and is completely self-service for pre-registered shoppers. Barcode scanning is used to enter the store and to select items for purchase.

Each country, market, demographic and lifestyle is different; it is the marketer’s job to tailor its messaging and strategies to these varying local trends. By spotting these patterns and the economic, social and technological impacts that influence them across the globe, FMCG brands can better prepare for the future and thrive in the present.

Data above comes from Kantar Worldpanel’s Brand Footprint Annual Report 2016

Alison Martin is the director of Kantar Worldpanel

To get weekly news analysis, job alerts and event notifications direct to your inbox, sign up free for Media & Tech Network membership.

All Guardian Media & Tech Network content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled “Paid for by” – find out more here.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion